I’m going to share a disturbing story from my undergrad that explains how messed up the business world is right now.

The setting: Econ 101. The class was full of nice Mormon kids. I was 18 and dressed like I worked at Hot Topic.

Our professor kicked off the semester with a game.

“Each of you have 5 dollars,” he began.

“We’re going to try to grow your money through a series of rounds.

For each round, you’ll each hold up on your hand the number of dollars you want to put into the pool alongside your other classmates. Then I’ll ask you to raise your hand if you want to take money out of the pool.

Every round, if no one takes any money out, the amount of money in the pool doubles and we go to the next round.

But if people decide to take money out, everyone who raised their hand will split the money that’s in the pool.

Now, I’ll let you discuss among yourselves for a minute, then we’ll start Round 1.”

Immediately, students began colluding. Everyone decided that if we all put the max amount of money into the pool each round, and we let it go on for several rounds, then we could all take out many multiples of what we put in. We just had to all cooperate.

After a minute, the game began. The professor asked how much people wanted to put into the pool. Everyone put in the full 5 dollars. And then when the professor asked if anyone wanted to take money out, everyone kept their hand down. Except me. I raised my hand, and took the entire pot for myself. Something like a 25x return on my 5 dollars, which would have taken a lot of rounds to generate the way my nice fellow students had proposed.

My classmates were pissed. They thought we’d all agreed to cooperate and not do exactly what I did. Especially not on the very first round.

But here’s the disturbing part.

My professor singled me out, “Now this guy is going to make it far,” he said. “He recognized that someone was going to eventually try to take the spoils for themselves, and so he might as well take them first.”

This was our introduction to Rational Self-Interest, the most powerful principle of Economics (according to my professor). In a system of trading, bartering, selling, and buying, people make decisions based on what is in their personal benefit—and they think it’s rational to do so even when the tradeoffs (e.g. screwing over your classmates) seem shitty.

This is the rationalization for doing selfish things: that it’s in your interest, and therefore it’s ok.

I was honestly horrified by this outcome. It shaped the way I perceived the rest of the semester, and my business career. I raised my hand because I figured out that it was the way to win a GAME. I didn’t know that this game was meant to indoctrinate my classmates and I. To teach us that it’s valid to deal with other human beings as if we’re in a zero sum game.

Perhaps it was my conscience. Or perhaps it was the looks of “how could you do this to us?” on my kindly Mormon classmates’ faces. But my professor’s singling me out backfired. Forever since, I’ve noticed rationalization in business more than I would have.

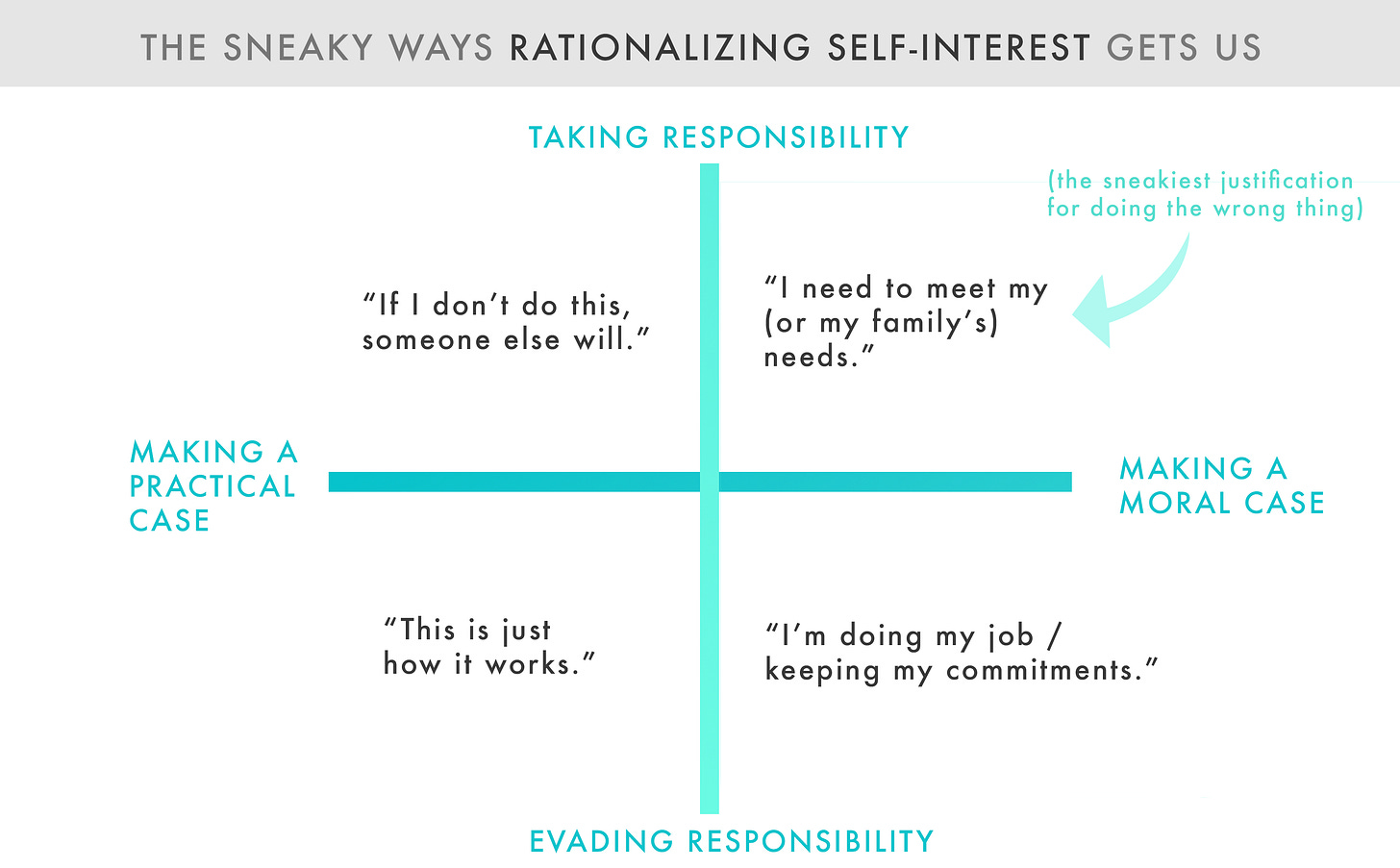

The generally fall into a few categories:

“If I don’t do this, someone else will.”

“I need to meet my / my family’s needs.”

“This is just how it works.”

“I’m doing my job / keeping my commitments.”

Some of these rationalizations are more sinister than others. I chart them like so:

Once you start viewing the world in terms of Rational Self Interest (or as I now call it, Rationalizing Self Interest), you’ll spot the opportunity to make shitty tradeoffs everywhere. And you’ll notice when people take those tradeoffs—and also when they don’t.

This week, The New York Times published a feature about mechanics and drivers who help fentanyl smugglers pack cars with drugs and sneak them into Arizona. Some of the people interviewed expressed remorse for the victims what they were doing, but said they needed money for their families and not to be killed by the cartel. That’s a very hard situation to not rationalize your own interests. Someone in this situation might even be called a victim themselves, were we to be charitable.

On the other hand, those running the business of drug smuggling appeared to express no remorse. “These operatives said that they were simply running a business, and argued that if they did not meet the American demand, someone else would,” wrote The Times.

This leads me to believe:

The further you physically are from the results of the tradeoff you’re rationalizing, the easier it is to rationalize.

The worst part about this? Those who understand Rational Self Interest can use it to manipulate people into doing their dirty work. Want to recruit people for your inhumane organization to put on a mask and terrorize immigrants like the Gestapo? Look for people who are drowning in student debt and offer to pay off their loans and feed their families.

In my own experience, the worse the organization is to the world, the more it plays on Rationalizing Self Interest. The most lucrative offers I’ve personally seen floated have come from the polluters, the businesses with toxic culture, and this one company in Florida that makes AR-15s.

“Yeah, the company isn’t the most environmentally friendly… but I need the health benefits.” (Translation: The company isn’t environmentally friendly, but I want to make myself feel better about being selfish.)

How hard is it to turn down a job with good benefits because it’s a bad organization? It depends on how privileged you are to have other options.

But if even a few more of us did the right thing when it was hard, the world would be a better place.

Rationalization Works Best When We’re Divided Up

Whenever an organization does something awful to its customers or to the world—say, increasing prices artificially and blaming inflation—multiple human beings with a conscience tend to have to sign off on the decision. How does that happen? Rationalizing Self Interest.

At the top: “I need the executive bonus so I can set my kids up financially when I’m gone.”

In the middle: “I can’t say no or I won’t get the promotion.”

At the bottom: “I’ve got to follow orders to keep my job.”

At each level, individuals rationalize doing the wrong thing, and so in total everyone does the wrong thing. (Which, ironically, lends the conscience some relief.)

Of course, the game of capitalist economics IS rigged against us. And we all have to make tradeoffs in our lives. The most we can ask is that we spot and stop Rationalizing Self Interest in the Big, Important situations, and that we do our best in the small ones. (We do have to feed our families; and yet there are other companies out there than the AR-15 guys.)

My fear, as the world gets simultaneously more interconnected, more divided, and more asocial, is that we as a society will be increasingly manipulated through Rational Self Interest.

Because when we have a personal interest in doing something, we’ll seek information and validation that it’s the right thing for us to do. And we’ll discount information that makes us feel bad about ourselves for doing the thing. We’ll burrow deeper into our filter bubbles. And there, where we’re divided and isolated, we can be manipulated harder by the truly bad actors.

But What Is One To Do?

Honestly, it’s hard. But we can say “No” to offers that play on Rationalizing Self Interest. We can say, “I’ll keep looking for options.” And if we truly value the long-term future of our communities, our families, our planet, and our system of economics and trade, we should be prepared to pay a price for that thing we value. If it costs you something to turn down a deal that puts the future in a worse spot, your “values” are actually values.

When making the long-term tradeoff is particularly tough, we can combat Rationalization by asking ourselves (or your favorite chatbot) for good reasons not to do what we’re thinking of rationalizing. Change the terms of the internal debate.

“Tell me good reasons why I should NOT do this.”

In this rigged system, we can still make meaningful choices. We can do things that we don’t have to do simply because the rules set us up to do them. For instance, in my role as a producer in TV and Film, I regularly go through project budgets with Line Producers, where the convention is to pay crew members the minimum amount dictated by the union. (Often these rates are down to the penny; e.g. $48.23 per hour for a Gaffer.) And when it’s a non-union job, Line Producers usually try to squeeze the crew costs down as low as people will say yes to. (And people who love movies are generally willing to say yes to very little pay.)

A couple years ago, my partners and I decided that we weren’t going to play this game. Whether the job was union or non-union, we were going to round up. We’d go far enough above the nickeling and diming that our crews could make a humane wage. And to boot, we set a goal of never going into overtime, so our crews can see their families. (This costs us, but I’m proud to say that we have only gone into true overtime on two workdays in the last two years.)

In the long run this begets loyalty and makes things better for people. It makes things better for our industry, which we’re hoping can sustain for a long time.

Am I saying that we make the right decision every time there’s a short-term vs long-term tradeoff to be had? Not at all. I’ve got a long way to go.

And in a way, seeing the world through the lens of Rationalizing Self Interest has helped me have more empathy. You realize that many people sincerely believe the rationalizations that are fed to them. People do have families to feed and lives to lead. And even I—whose eyes were opened to Rationalizing Self Interest decades ago by a dubious Econ 101 professor—still rationalize

And yet, we’re adults here. If we’re falling for Rationalizing Self Interest we need to admit to ourselves that being selfish is sacrificing our kids’ long term for our own short term. And the further we charge into the 21st century, the more I’m convinced that the sacrifices we make—or don’t—are for the survival of the entire planet.

Thank you so much for reading!

—Shane

An award-winning business journalist and Tony-winning producer, Shane Snow is the bestselling author of Dream Teams and a renowned speaker on leadership, innovative thinking, and storytelling.

Bro where was this version of Shane when we got the first offer to buy Contently

Great article. Thanks, Shane.