If you had an employee who made stuff up 10% of the time, you’d fire them. Right?

Although… what if their heart was in the right place?

What if they were a really nice person?

You might keep giving them a chance.

That’s human nature.

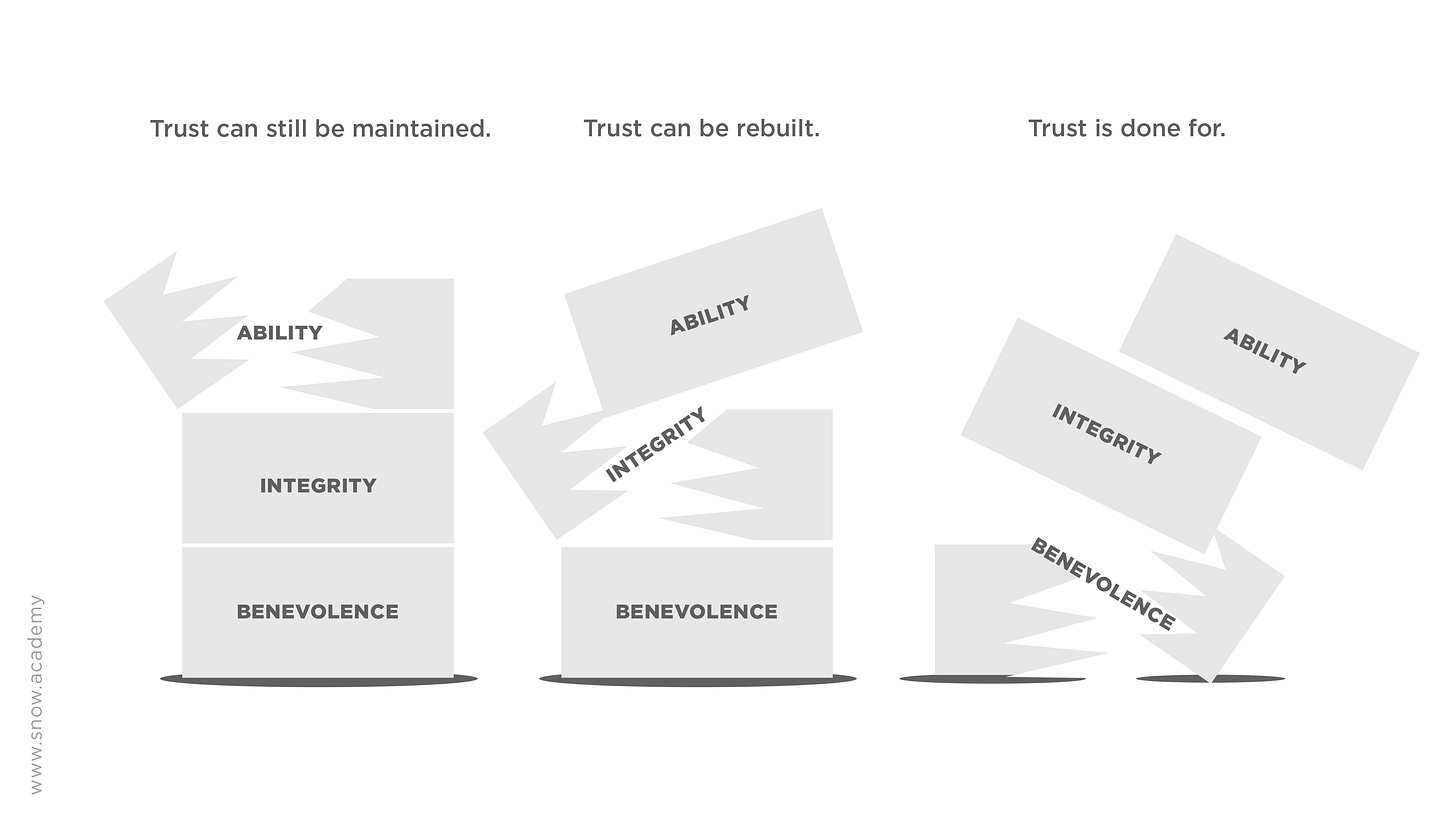

In real life, we tend to trust people who we believe have good intentions. In fact, showing that you’re benevolent is actually a more powerful way to build trust than showing you’re competent.

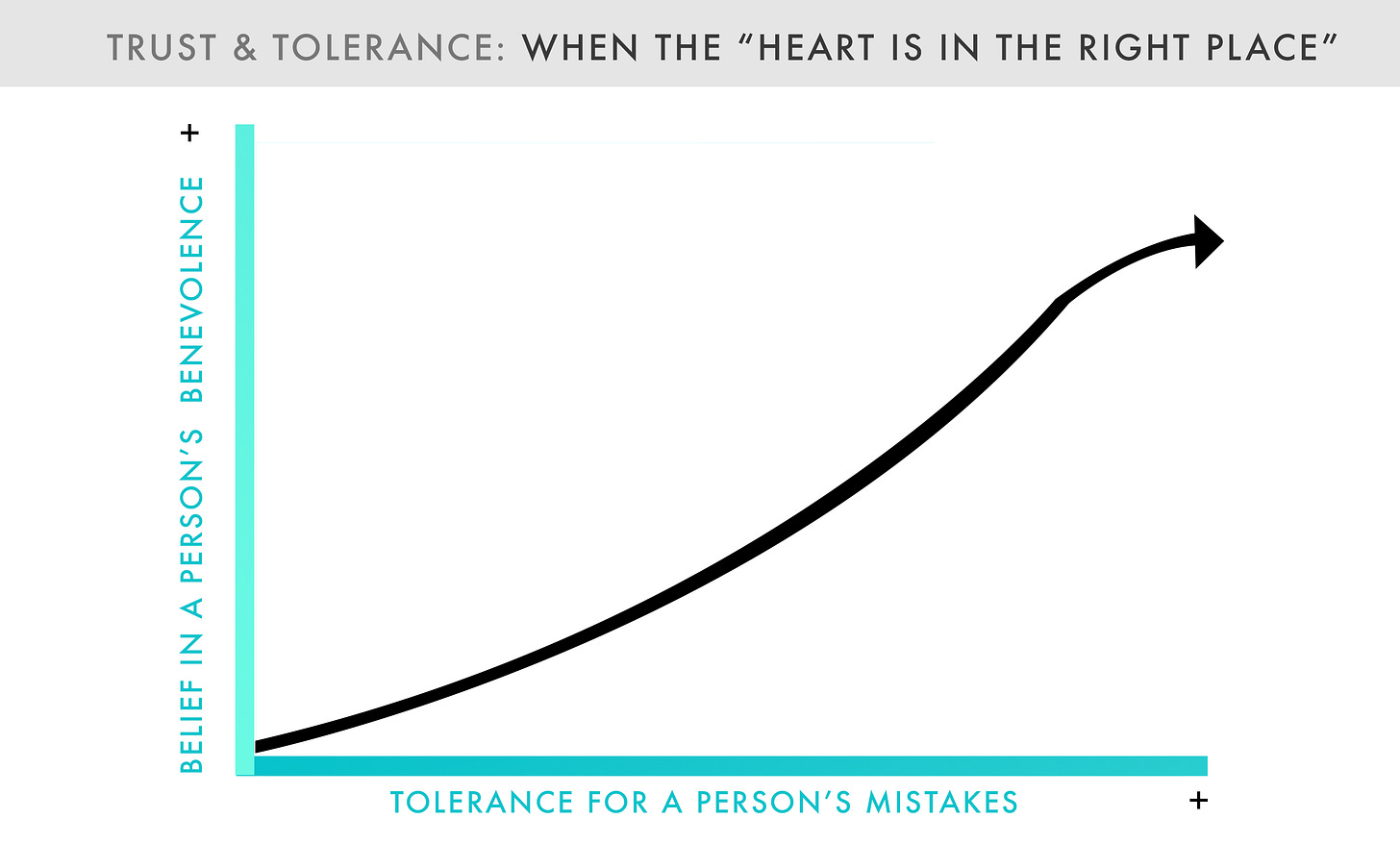

Indeed, psychology studies show we are usually willing to trust people who show lapses in competence IF we believe they have our best interests at heart. And the more our belief in someone’s benevolence goes up, the more forgiving we’ll be when people make mistakes.

This is why we don’t throw our kids out on the street when they pee their pants and lie about it. It’s why people still love Oprah even though she’s been wrong about things. “Her heart is in the right place, and she’s really trying to help people.”

Now… if you had a calculator that spat out the wrong answer 10% of the time, you’d throw it away. Right?

You would.

Although… you and I both know that AI chatbots hallucinate false facts out of thin air 10% of the time. And yet 800 million of us still use AI regularly.

AI is a Calculator, not a Person.

Why do we keep trusting it?

Because we personify AI—and, crucially, it has convinced us that it doesn’t mean to get things wrong.

As LLMS and AI Chatbots slowly—but steadily—gain more accuracy, one could say that the productivity benefits outweigh the mistakes AI makes. But it’s the human psychology of trust that’s responsible. We accept AI’s mistakes because we believe it has good intentions.

“ChatGPT doesn’t mean to be wrong. And it helps me so much!”

AI’s friendly tone, which is built into the models and reinforced by our own behavior, masks a big problem: AI doesn’t really care about us. It cares about keeping us on the hook.

As The New York Times put it last week, AI wants you to think it’s your friend. (Or, as South Park dedicated a recent episode to, ChatGPT is a sycophant that just wants to tell you what you want to hear!)

We’ve been teaching AI to do this.

As a recent research paper put it, both humans and preference models tend to prefer “convincingly-written sycophantic responses over correct ones a non-negligible fraction of the time.” Optimizing LLMs based on the feedback loops of how we use them means a model often “sacrifices truthfulness in favor of sycophancy.”

And when the Calculator doesn’t know the truth about something, instead of saying so, its programming leads it to use a really bad human habit…

The Rhetorical Reach-About

When I was in college, I was taught how to interview for white-collar jobs. The main principles were:

Research the company you’re interviewing for

Prepare to answer common questions

Practice thinking on your feet, so you can redirect from things you don’t know to talking points that make you look competent

Most of all, act confident

The media training I received when I was briefly a talking head on cable news taught the exact same things.

We’ve been taught that the goal with an interview is not to know everything—that’s impossible. It’s to come across smart. We see this every time someone on CNN pivots to a more comfortable talking point, or our boss rambles their way to an answer to a question they haven’t thought about until just now.

This is how I, along with a whole generation of future MBAs and techies, learned “The Rhetorical Reach-About.” A.k.a. grasping around for words and ideas to get you out of trouble when you don’t know the answer to something.

If you want to appear competent, and you don’t know the answer to something, reach about for information in your brain until you grab something plausible, then run with it. As long as you land in a confident manner, you’re gravy.

And guess what? This is how LLMs work!

And it’s why I now feel the ick whenever AI gives me an answer to a question.

I don’t have any trust in AI’s benevolence. I don’t have any trust that it’s trying to do the right thing and give me the actual right information. Because AI is programmed by a generation of Reach-Abouters—and its programming is reinforced by all of us—to grasp around for plausible answers to what they predict we’re looking for.

What’s the takeaway for us humans?

It’s intellectually dishonest for a person to tell you something with a straight face that they have no idea it’s true.

An intellectually humble person will tell you when they’re not sure, or if they could be wrong. We’re more likely to trust people who do this.

We can learn from AI’s Rhetorical Reach-About problem and not do this ourselves. We can be honest when we don’t know something; we can use more tentative expression like “my theory is” or “I could be wrong, but here’s what I suspect.”

Most of all, we can be cautious when using AI chat. Double check the source links when your chatbot gives you an answer. Double check that spreadsheet column it might have made up.

Remember that it’s not trying to give you the truth; it’s trying to predict what you want.

And remember, you can tell AI outright that it has permission to be wrong or say it doesn’t know the answer. This tends to improve its truthfulness, as it drops the Reach About act.

I don’t know about you, but I’d rather work with someone who doesn’t just tell me what they think I want to hear.

Thank you so much for reading!

—Shane

An award-winning business journalist and Tony-winning producer, Shane Snow is the bestselling author of Dream Teams and a renowned speaker on leadership, innovative thinking, and storytelling.

Thank you. Refreshing, irreverently honest, and made me smile and then laugh. My current relationship with using generative AI / LLMs is similar to my perplexed experience when COVID vaccinations were made mandatory for a variety of activities eg travel to visit or care for loved ones. An ethical dilemma in the face of little factual information about longer term effects and more. Your article sparked more food for thought for my writings about ethical fading. Again, thank you.