This one crappy chart changed the way I think

I TOOK TWELVE FULL PAGES of notes from Nir Eyal’s new book Indistractable when I read a draft copy of it last fall. The book promised to help me “get real” with myself about my distractions, procrastination, and subtle addictions—and ultimately to help me, as Nir puts it “be able to do what you say you will do.”

But the first thing the book actually did was help me solve my email problem.

The second—and I admit, my favorite—thing it did was teach me something new about intellectual humility. If you’re getting this email, you are by now overly aware how important this topic is to me. :)

A key principle in Nir’s book is called “Proximate Cause,” and it explains a lot about why people don’t change when they should. (I.e. why we often aren’t intellectually humble.)

The theory of Proximate Cause says that humans are bad at identifying the real reasons we do things. And it’s not because we can’t dig deep. It’s because we tend to only dig until we find the closest rationalization—and then we stop. We don’t dig deeper to the REAL reason underneath our rationalizations.

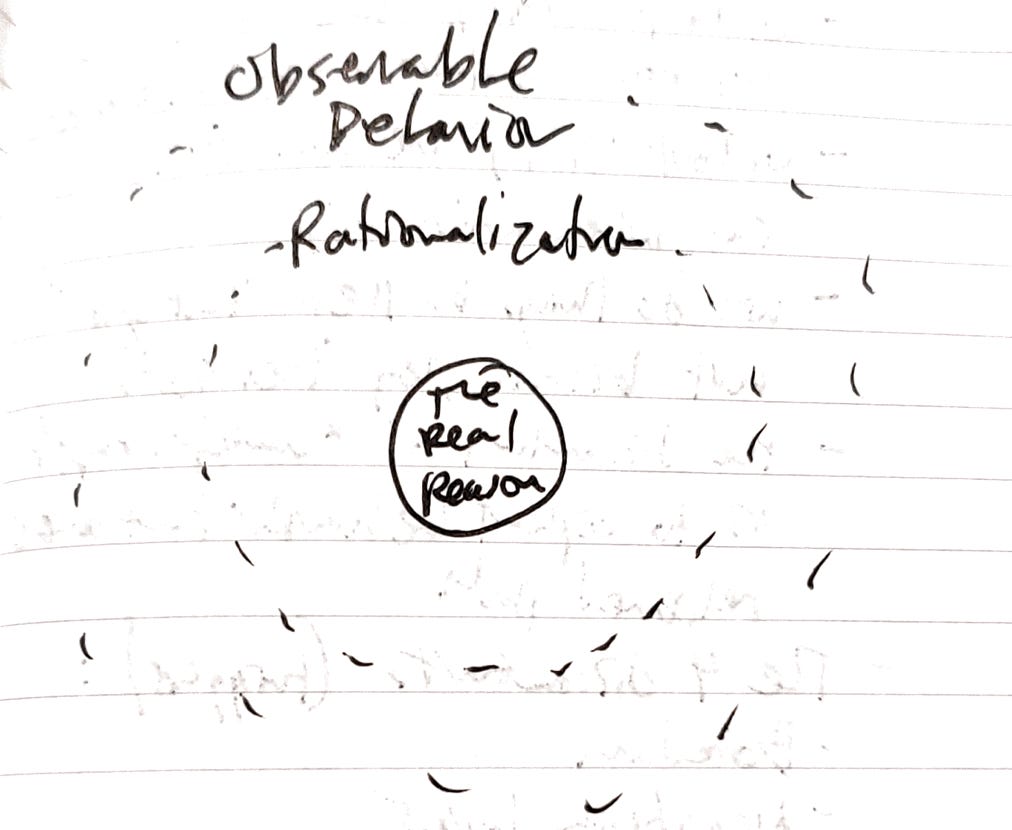

Here’s my crappy chart I drew in my notebook summarizing this simple, but powerful principle:

(If you can’t read my bad handwriting, it says “Observable Behavior < Rationalization < The Real Reason”.)

We say we’re watching TV (Observation) because we’re tired (Rationalization), but The Real Reason is we don’t want to think about the hard conversation we need to have at work tomorrow.

We say we have an email problem (Observation) because we get so many emails (Rationalization), but The Real Reason is we don’t have a thoughtful, deliberate process for dealing with the reality of email overload. (And the Real Reason for that might be because we’d rather not do the hard work of thinking about how to solve it, or we think we’ll fail, or we think we’re helpless, or something else.)

Nir writes that it’s like when you play pool: You hit the white ball with the stick, and that ball hits another ball into the pocket. The white ball is not the REAL reason the other ball goes into the pocket.

Much of the time, we take our observable behavior—say, “I got snippy at my coworker at the offsite”—and we claim that the reason was something external—because the coworker said something annoying or stupid.

But this “rationalization” actually masks The Real Reason—Perhaps going along with our coworker’s idea might mean we’d have to do a lot more work we don’t want to do. Or if they’re right about the thing they’re talking about, it might mean we were wrong earlier, and that would bruise our ego.

So we treat them snippily, so they can lose the debate.

It’s not bad to watch TV to turn our brains off sometimes, but if we don’t identify the REAL reason we’re doing it, we’re giving up a little bit of power over ourselves. It actually is a bad idea to get snippy at our co-worker if the real reason we don’t want to listen to them is because we don’t want to change.

My intellectual humility research shows that the #1 thing that prevents most people from being truly intellectually humble is not being able to separate our ego from our ideas. The more we abstract ourselves away from the real reasons we do what we do, the harder it is to do that.

In real life, it’s ultra common for us to pay more attention to—and blame—that second cue ball for our behavior and not dig deeper into what’s behind it. And that prevents us from exercising intellectual humility.

Getting “real” with ourselves is easier said than done. I recommend Indistractable as a great first step on that journey.

Meantime, here’s to thinking a little bit harder about why we do what we do—and CHOOSING to do it!

Much love,

Shane

P.S. If you’d like to take a more advanced step on the journey of intellectual humility (and becoming a great team player in general), I’m soft-launching the Snow Academy online course on Dream Teams this month. Be among the first to check it out here!