What We Learn About Decision-Making From The Counterintuitive Success of Family Businesses

A new essay by Shane Snow

Contrary to popular belief…

If you look at a bottle of Bacardi rum today, two things will stand out: A black and red insignia of a bat, and the words “Established in 1862.”

This is a brand that has weathered many storms. The Industrial Revolution. The Great Depression. The Cold War. The Digital Revolution. And unlike most brands lucky enough to survive 150 years of disruptions, Bacardi also survived the Cuban Revolution. Both of them, actually. First, the revolution against Spain, then the popular people’s revolution that brought Fidel Castro to power. Bacardi funded and/or fought for both, then fled Cuba when Castro betrayed his allies and became a dictator.

Through all this, Bacardi has remained a family business. We're on the seventh generation of Bacardis since founder Facundo Bacardi Masso began distilling rum in Santiago de Cuba.

The remarkable success of this family business bucks common wisdom in the business world. Namely, that most family businesses are doomed by the third generation. Various versions of the same saying go that the first generation generates the wealth, the second enjoys it, and the third squanders it. And if all we did was believe the rumor mill and watch Succession, we could just nod our heads and move on.

Yet, research shows that the exact opposite is true. Remarkably, the success of the Bacardi family business is more rule than it is exception.

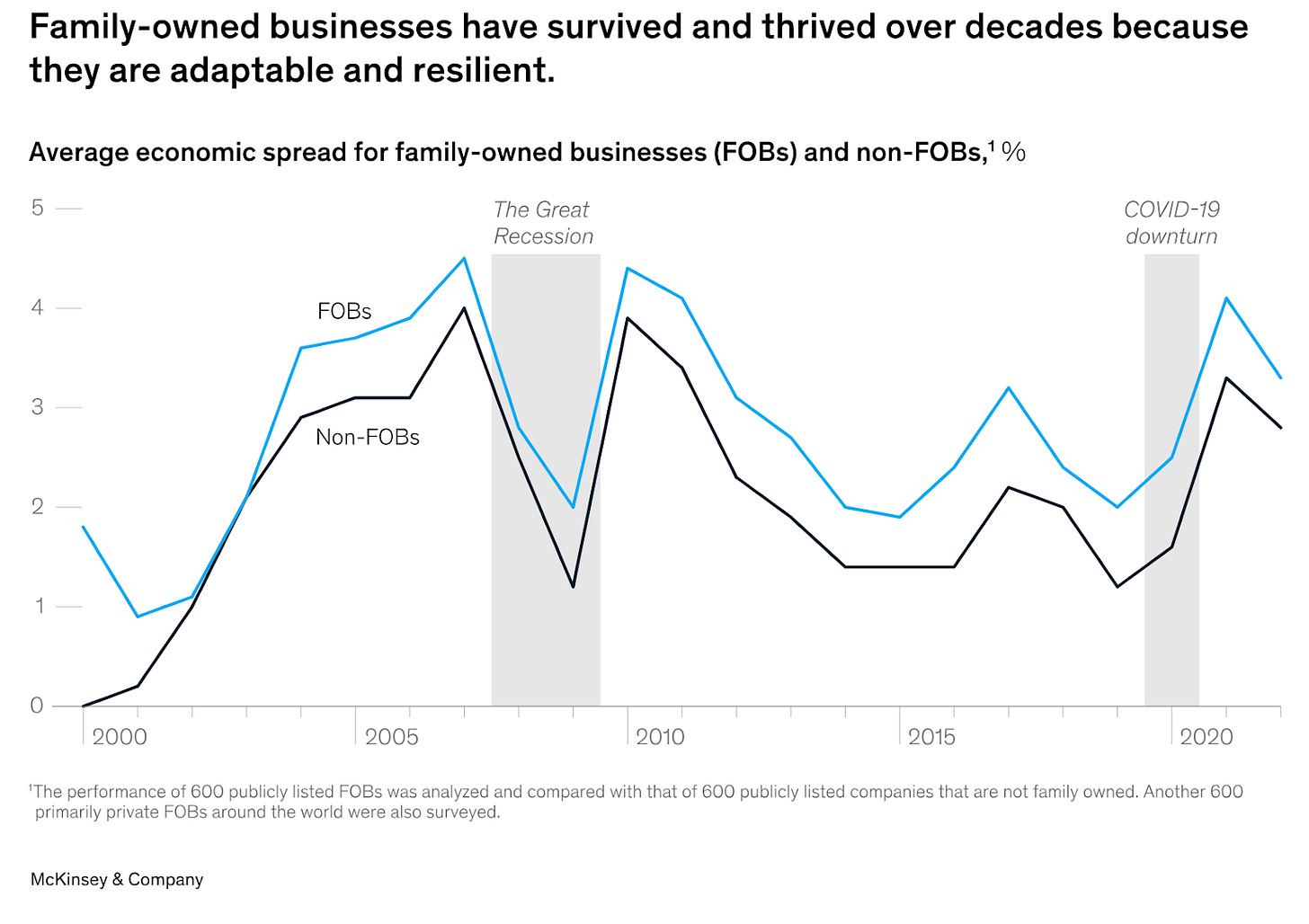

In a large-scale 2023 report, McKinsey & Co. laid out decades of business performance data showing that Family Owned Businesses (FOBs) consistently weather market downturns and stick around longer than others.

It’s the non-family businesses that are more likely to go kaput within three generations.

Why is this?

Before and after the overthrow of Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista in 1959, the Bacardi Rum Company was one of the most influential businesses in Cuba. Its CEO during the revolution, Jose Bosch (husband of Enriqueta Bacardi) was the most respected businessman in the country. The company had nearly made it to 100 years old, had expanded its factories to Puerto Rico, and was shipping rum around the world.

Bacardi had supported the rebellion against Cuba’s brutal dictator. But in the aftermath, Castro consolidated power, killed his rivals and detractors, and began driving Cuba into the ground. It was not the democratic outcome revolutionary supporters had hoped for.

Eventually, Castro seized Bacardi’s factories, and the Bacardi family fled the country.

What happened next, though, is peculiar.

One could imagine a company in this position making drastic moves. Cutting costs, regrouping around the remaining headquarters in Puerto Rico. Looking for a buyout, etc.

Bacardi did something unexpected for a corporation. Instead of tightening the belt, Bacardi spent its time and resources helping its employees and their families and friends move to the United States and get on their feet. They even set up a phone number that Cuban exiles could call upon arrival in Miami. A Bacardi family member would show up and help you find housing and work (and not always for the Bacardi company).

I’m convinced that Bacardi is the thriving, massive company it is today because of counterintuitive decisions like this. Had the company cut its losses and not invested in the long-term care and feeding of its employees when the going got tough (to put it mildly), it’s likely that Bacardi would have sold to some other brand long ago, or would now be defunct. Instead, it's continued to enjoy high retention, brand loyalty, and a resilient business.

A Wise Decision-Making Exercise You Should Try

Think about a big decision you have coming up. (Or one you’ve made in the past if nothing comes to mind.) Here’s a recent one of mine: My apartment lease is up soon; where should we move?

If it’s an important decision, you’ve probably thought it through a bunch of times. You might have even made the smart move of asking the question in terms of second-order effects. E.g. Where should we move that won’t make things harder with our two-year old kid?

Now think of this decision in terms of a 20-year timeline. What could the consequences be for this decision in 20 years? Or perhaps better put, what decision could lead to the best outcome 20 years from now? E.g. Where should we move in order to set our kid up for the best outcome when he’s 22?

Obviously we can’t predict the future. And this may seem like a crazy question to be asking when it comes to moving apartments. But the exercise itself is the point. Thinking through not just the long-term ramifications, but the REALLY-long-term potential effects of our decisions, helps us to be more resilient and adaptable. I might really want to buy a loft in the East Village right now, but I bet I'll set my kid up better 20 years from now if we move within walking distance to a good Montessori daycare and keep renting. (Past me might throw up in his mouth to hear this.)

And that’s what the research on successful Family Owned Businesses shows. Among several patterns one stands above all else: a focus on long-term resilience and adaptability over short-term profits or savings.

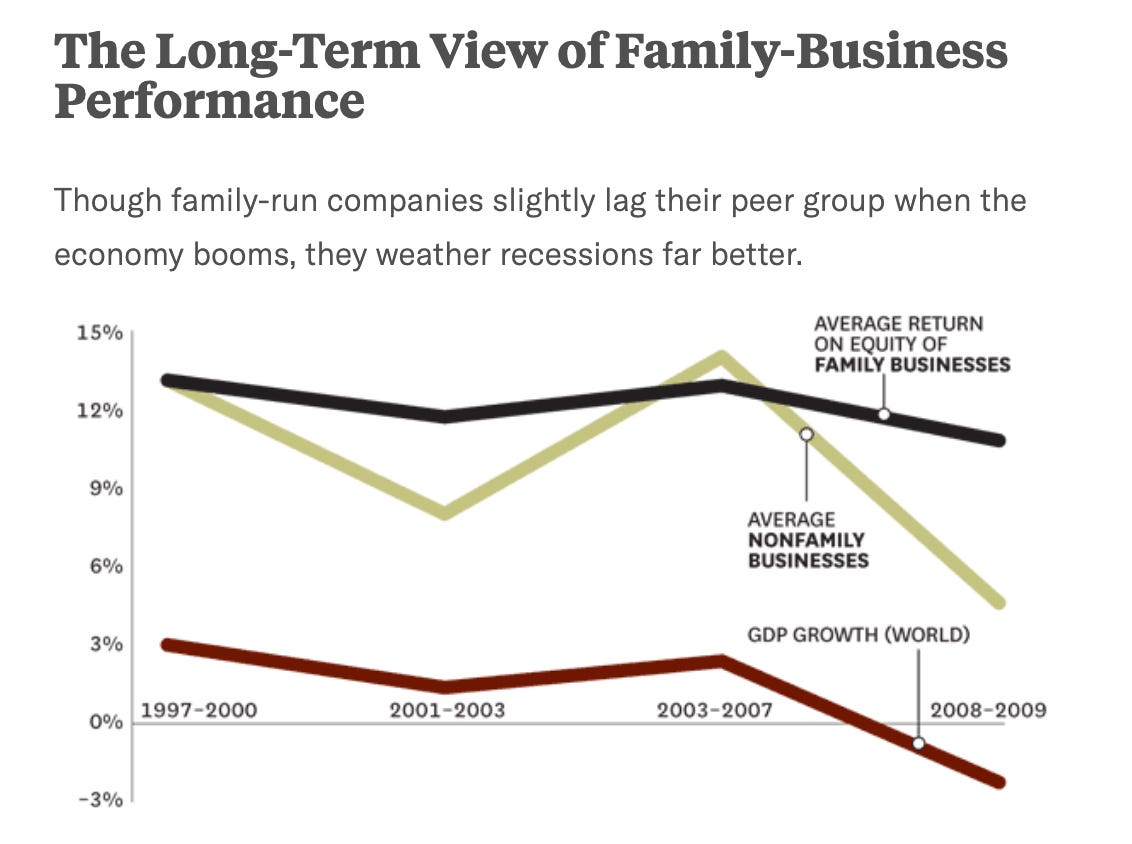

Harvard Business Review reports that family businesses may not grow as quickly during boom times, but they tend to be more stable during hard times for this very reason.

HBR says that “the simple conclusion we reached is that family businesses focus on resilience more than performance,” but McKinsey takes the conclusion one step further. According to their study,

The secret to family business longevity comes down to decision-making that takes a long view, yet takes place efficiently.

Taking The (Really) Long View In Decision-Making

I’m convinced that most business leaders aren’t selfish. The selfish ones are out there, but I’ve observed that the leaders at the best companies I’ve consulted for tend to care deeply about their teams and their customers.

And yet, corporate leaders are usually incentivized by short-term metrics. Profits this quarter, this year mean bonuses for them (and, ideally, their team). Whenever it’s decision time, that means tradeoffs—certain rewards now versus possible rewards later.

Reality is that even leaders who think longer term—say, 5 years out—when making strategic decisions for their companies, are still thinking shorter term than the leaders of Family Owned Businesses. As HBR puts it, “Executives of family businesses often invest with a 10- or 20-year horizon, concentrating on what they can do now to benefit the next generation.”

We learn from psychology that one of the downsides of an inflated ego—which places too much focus on oneself—is that the importance of others and what they can contribute gets obscured, and therefore reality gets obscured.

Taking a really long view (a la 20 years) can help bring reality into sight.

And so family businesses tend to make decisions that are less biased in favor of the personal priorities of the current executive team (bonuses, quarterly targets, resume building), and more biased toward the business sticking around for a long time.

Can a business have it both ways? Certainly. But when these two priorities conflict—personal aims of executives and long-term success of the larger business—the moral dilemma of “which good thing do we choose” naturally will lead most businesspeople to prioritize success that can be measured in the short run. After all, who knows if you’ll even be at this company in 5 years, let alone 20? Rational self-interest would say it’s better to show that things improved during the 2 years you were in charge than to make sure the business maximizes its chances 20 years from now.

But if you’re the CEO of Bacardi circa 1960, you’re thinking about the business your grandkids will inherit. So you use your own money to help your factory workers and farmers leave Cuba and resettle in Miami or San Juan.

You make the hard choices to set things up so that a lot of people can have stability in the future, rather than squeezing out what money you can right now.

Making Decisions Efficiently

Rapid, efficient decision-making is a topic I’ll explore in depth in a future essay in this series. But suffice it to say, the structure of a Family Owned Business lends itself to quick execution. Committee votes tend to be less of a thing.

Of course, hasty decision-making is not good for business. The best leaders are those who can source information from diverse sources, push people to push their own thinking, make calls, and then admit quickly when those calls were wrong. The goal of creating a generation-spanning business can naturally push a leader into some of this behavior.

Now, I’m not saying that you need to quit whatever you’re doing and join (or start) a family business. What I’m saying is that the common wisdom that working with family is a bad idea simply isn’t true—and we can learn from what makes family businesses great.

Which brings us to that bat logo on the Bacardi bottle. It’s a curious mascot in modern times. But in the 1800s in Catalonia, from whence Facundo Bacardi immigrated to Cuba, the bat symbolized faithfulness and self-confidence. Bats fly together, after all. And they fly in the dark without hitting anything.

No matter the obstacles that appear in their path.

Thanks for reading. Make a great day!

—Shane

Great piece. Also this made me look up someone I went to high school with who was a Bacardi heir and she’s … the director of PR at Kargo?

Rarely if ever have I ever thought about the long term consequences of moving. As I think back on those decisions, had I considered the long term consequences, I'd have likely done something different. Great advice for most all areas of life decisions